- Authored by Colby Colona

June 15, 2021

Earlier blog entries have mentioned “LAMP” testing, but what exactly is that? So let’s shine a light on the subject! (You see what I did there?)

A major component of our operations is collecting mosquitoes (to read more about surveillance, click HERE). I have previously covered what happens to most collected mosquitoes (for a review, click HERE). Still, at TMAD, we like to go big or go home, which is why in 2018, our board of directors voted to invest in implementing our own in-house West Nile Virus testing.

We were the first mosquito control district in the state to incorporate this specific technology into our routine operations, and we are especially proud of this!

That’s nice and all, but what is it?

LAMP stands for “loop-mediated isothermal amplification.” It’s a mouthful, but the basic idea is simple: isolate and amplify genetic material to show the presence of the West Nile virus. By having this equipment and technology in our own lab, we eliminate turnaround time and can even test mosquito samples on the same day as collection. This is a big deal for public health! During peak West Nile virus season, we can essentially set out a trap, collect extra mosquitoes from that trap, and test them as soon as they are brought back to the lab. Then, instead of waiting a week or two weeks for results from the state lab, we can know the same day if we need to send out our trucks or our plane to a specific area. This allows us to be more “proactive” rather than “reactive.”

The Process

LAMP testing is all about the genetic material within the cells or ribonucleic acids (RNA). Ribonucleic acids are present in living cells, and the general purpose is to carry instructions about making proteins to your cell’s DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). Once mosquitoes are collected from a trap, this RNA must be extracted. This means that the rest of the cell needs to be essentially dissolved so that the RNA is easily isolated.

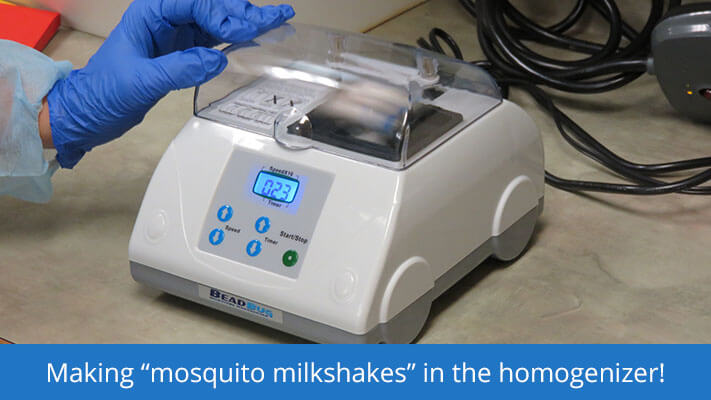

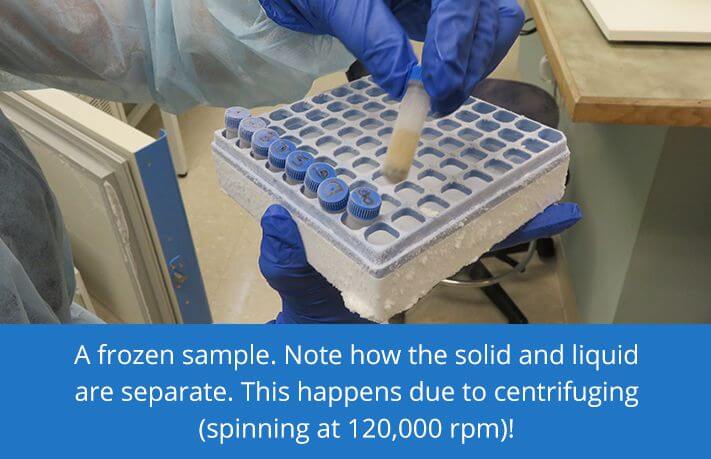

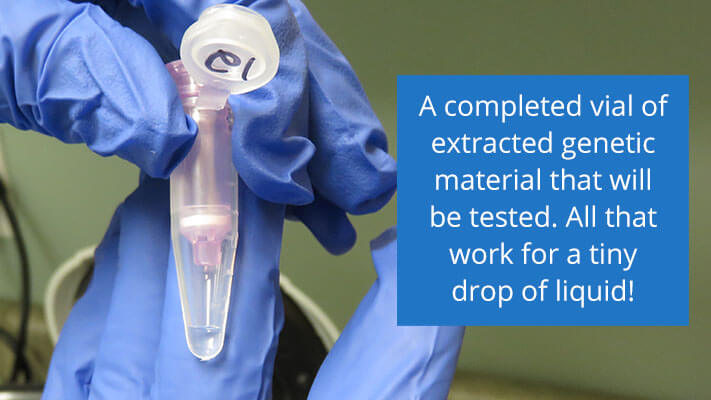

This is done by pulverizing the mosquitoes (making a mosquito milkshake!), separating the solids from the liquids by centrifuging, taking out some of the “slush” (i.e., homogenate), and then washing away the “unnecessary” parts of the cell to get the RNA by itself.

This is the most labor-intensive part of the test and usually takes about 45 minutes to an hour, depending on how many samples are being extracted. Cells are stubborn little things!

After the extraction has taken place and the RNA is isolated, we must then amplify it to make it easily visible to the processing equipment. Finally, dyes and primers are added to enable the RNA to show up in the last step-the all-powerful Genie!

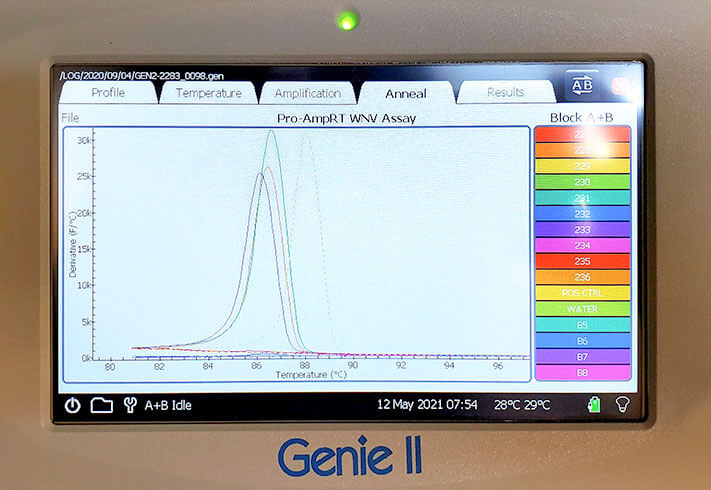

The Genie is the little machine that does all the final analysis and clearly reports positive and negative results. It usually takes about thirty minutes for this processing to complete.

How do you know the test was done correctly?

In every test run in our lab, we also run a positive and negative control. What does that mean? For every group of samples tested, we also run one sample that we know will be positive by adding specific reagents and one test with only water added instead of mosquito RNA to know it will be negative. If either shows anything other than the expected positive or negative result, we know that the test was possibly contaminated and will retest. This ensures that we are only working with the most accurate results better to serve the public health needs of our citizens.

You should see four “peaks.” These represent a positive result for the presence of the West Nile virus. The dotted yellow line is a positive control, and though hard to see, a light green line flat on the X-axis represents negative control. This demonstrates that the test is not contaminated and the results are accurate.

How many samples can you run at once?

We can run up to 16 samples at once, including the positive and negative controls. We can do this twice a day if we need even more samples tested, for a total of 32 samples a day. We are exploring our options for increasing this number in the future.

Final thoughts

We strive to use science-based evidence to make our treatment decisions. LAMP testing is just one facet of the ongoing Integrated Mosquito Management strategy we use in our operations. Knowing where the West Nile virus is located quickly, we can better target our treatments and keep our citizens safer!

We strive to use science-based evidence to make our treatment decisions. LAMP testing is just one facet of the ongoing Integrated Mosquito Management strategy we use in our operations. Knowing where the West Nile virus is located quickly, we can better target our treatments and keep our citizens safer!

Have more questions or want to chat? Call our office, and we will be happy to help!